¶ Rousseau's Wills

In The Social Contract (1762), French political philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau drew a crucial distinction between different kinds of will:

- Individual Will – A person’s private wants and needs.

- Factional Will (the will of particular associations) – The agenda pursued by an organized subset of the population.

- General Will – A principled compromise of all Individual Wills, expressing what is right for the whole community, not merely what is popular.

While Individual Will is raw personal preference, the General Will is an aspirational, moral compromise of all the Individual Wills that reflects what free and equal citizens would choose if they deliberated sincerely as members of a shared community. General Will is roughly equivalent to the ideal of the common good.

Factional Will is a subset of Individual Wills that are working for the advancement of a common cause. Factional Will is what is measured by opinion polls, market indicators, as well as elections. Factional Will reflects what is popular, not necessarily what is right or fair.

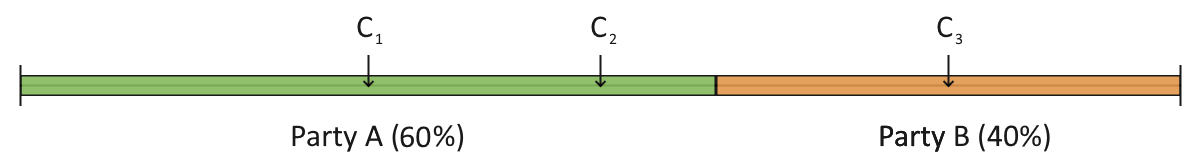

The difference between Factional WIll and General Will is apparent on the ubiquitous left-right spectrum in US politics. Assuming there are two parties across the spectrum with the following support:

Party A has its own Factional Will which would be located politically in the party’s center or around C1. Party B’s Factional Will would be the same and represented by C3. Since Party A would likely win an election, they would implement their party platform which would be around C1.

However, the General Will is a reflection of the population and so it is closer to C2, the perspective of the median voter. However, this will never be implemented, regardless of which party is elected.

Taxes can also illustrate how scope and perspective shift between the three wills:

- Individual Will: “I do not want to pay my taxes.”

- Factional Will: “That group should pay higher/lower taxes.”

- General Will: “Everyone should pay their taxes.”

¶ The Justification of Government

For Rousseau, a government is morally justified only insofar as it identifies and implements the General Will. In fact, he claimed a government not in pursuit of the General Will was illegitimate. This mirrors the modern ideal that our democratic government exists “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

By these ideals, the United States falls far short. Our system produces Factional Will almost exclusively.